Silents nights: DVD stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings

Monday | November 28, 2011 open printable version

open printable version

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts

Kristin here:

The year 2011 has been a good year for silent cinema on DVD. In time for the holiday shopping season, here’s an overview of some of the highlights.

One-stop shopping for the latest restorations

In the past we have recommended films released on DVD through the Munich Film Museum’s Edition Filmmuseum. We haven’t really emphasized enough, however, what a major resource this site is for film enthusiasts interested in restorations of older films and new editions of hard-to-see modern films (like the work of James Benning). Edition Filmmuseum sells not only its own impressive series of releases but also DVD editions of restorations by other major national European archives. Its website is available in German and English versions, and it is as easy to sign up and order DVDs there as it is through Amazon. The DVDs on offer can be browsed via a number of different categories, such as “Silent films,” “German movies,” and “Danish classics.” Releases from Lobster Films and Flicker Alley are also available through Edition Filmmuseum. Have a look at its forthcoming releases here. North American educational institutions seeking public performance rights for many of these and other titles should contact Gartenberg Media Entertainment.

Scandinavia comes on strong

Danish and Swedish films show up fairly regularly on DVD these days, but Norwegian films are rarities. This year, though, there are two of them.

The Danish Film Institute continues to release the films of Carl Theodor Dreyer. This time it’s a pairing of Elsker Hverandre (Love One Another, 1922) and Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal, 1926), also available in Blu-ray. (See below.) I have to admit that these are not among my favorite Dreyer films, and I don’t think many would put them alongside his best works. Still, Dreyer is one of the great masters of world cinema, and anyone seriously interested in film history will want to see these. Back when David was working on his book on Dreyer, we went to Copenhagen and saw these at the Film Institute. They were incredibly rare, and it was a privilege to see them. Now, they’re available to all. Check out the Institute’s entire list of restored Danish classics on DVD here.

[Dec. 16: Archivist Jan-Christopher Horak has recently blogged about Elsker Hverandre.]

The Bride of Glomdal is the first of our two Norwegian features. Dreyer worked outside Denmark a number of times. In the summer of 1925 he shot this film in Norway. His next film was to be La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

The second is Laila, a 1929 Norwegian feature, also with a Dreyer connection. Its director, George Schéevoigt, had been Dreyer’s  cinematographer for some of his early films: Leaves from Satan’s Book, The Parson’s Widow, Once Upon a Time, and Master of the House. Laila bears no sign of Dreyer’s influence, but its images, shot in the snowy mountains and valleys of the arctic regions of Norway, are gorgeous.

cinematographer for some of his early films: Leaves from Satan’s Book, The Parson’s Widow, Once Upon a Time, and Master of the House. Laila bears no sign of Dreyer’s influence, but its images, shot in the snowy mountains and valleys of the arctic regions of Norway, are gorgeous.

Like many features made in countries with no real established film industry (Laila’s footage had to be processed and edited in Copenhagen), Laila exploits both national literature and landscapes to distinguish itself from the Hollywood films that dominated European theaters. It was based on an 1881 novel by J. A Friis, Fra Minmarken, Skildringer. Friis strove to promote the rights of the indigenous Sami people (sometimes known as Lapps). The story follows the heroine, Laila, from infancy to adulthood. The first half of the film succeeds in giving a distinctly non-classical feel to the story. Laila is lost in the snowy wastes when wolves attack her family as they travel on sleds. She is found and nurtured by a childless Sami couple who come to love her but return her to her parents when they learn her background. The scene of the return is handled in a subtle and moving fashion. As the grieving parents console each other on Christmas Eve, Aslag, the baby’s foster father, enters at the left, with the tree blocking the door. He crosses to appear at the center and puts the child beside the presents under the tree:

A cut-in to Aslag shows him struggling with his emotions before turning to the parents and declaring, “Tonight all should be happy.” The mystified parents stare at him uncomprehendingly before he explains that he had found their daughter:

Once Laila grows up, the film turns into the more typical romantic triangle. Still, its epic landscapes and focus on a little-known ethnic group make it quite appealing, and the print itself is gorgeous. Flicker Alley has provided a rare opportunity to step outside the more familiar filmmaking countries and explore a bit. Our friend, the fine Danish film historian Casper Tyberg, has provided a helpful text in the accompanying booklet.

Casper also provides a commentary for The Criterion Collection’s release of the restored version of Victor Sjöström’s The Phantom Chariot. (It’s number 579 for you Criterion completists–but you already know about this disc anyway.) I won’t say much about it, since it will inevitably show up in our year-end list of the ten best films of 1921. Here I’ll just note that it’s also a beautiful print, with impeccable tinting and toning that don’t darken the images to the point where the composition is obscured–something I’ve seen too often in recent DVD releases of silent films. The frame above shows the opening scene, with its masterful control of lighting. I was disappointed that the supplements stress Sjöström’s influence on Ingmar Bergman. It may sound heretical, but Sjöström seems to me the better director, and I wish there had been more on his career.

One of the most obscure of German Expressionist films

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts (“From Morning to Midnight”) is an early Expressionist film. It came out the same year as Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. It’s based on a play by one of the major Expressionist dramatists, Georg Kaiser, and directed by one of the major Expressionist stage directors, Karlheinz Martin. The problem is, it never got released in Germany.

Most of the classic Expressionist films are, like Caligari, horror films that motivate their stylization through genre. Von Morgens bis Mitternachts adheres to the subject matter of Expressionist theater, which was vehemently critical of modern society. It centers around a downtrodden bank clerk who suddenly rebels against his apparently happy family life and good job, stealing a huge sum from the bank and trying to run off with a glamorous rich woman who visits the bank. Rejected by her, he wanders away to spend the money in frivolous pursuits.

It’s no wonder that German distribution companies shied away from releasing the film. Its only known theatrical screenings were in Japan, where one nitrate positive print survived. I saw an archival copy years ago. It was an impressive film, more extreme in its stylization than Caligari or even Robert Wiene’s second Expressionist film, Genuine. (All three films were released in 1920.) Unfortunately it had no intertitles, which made it seem all the more radical.

In 1987 censorship records were discovered that allowed the Munich Filmmuseum to reconstruct the intertitles and create the restored version that now has been released on DVD. It’s a significant film, not only as an artistic achievement but as a record of stage  Expressionism of the 1910s. Few plays of the era were filmed, most importantly this one and Jeopold Jessner’s 1923 film Erdgeist, adapted from the play by Frank Wedekind and starring Asta Nielsen and Albert Bassermann. (The play was adapted again by G. W. Pabst as Pandora’s Box, starring Louise Brooks, in 1929; wonderful though that version is, it retains little of the radical Expressionism of the original.)

Expressionism of the 1910s. Few plays of the era were filmed, most importantly this one and Jeopold Jessner’s 1923 film Erdgeist, adapted from the play by Frank Wedekind and starring Asta Nielsen and Albert Bassermann. (The play was adapted again by G. W. Pabst as Pandora’s Box, starring Louise Brooks, in 1929; wonderful though that version is, it retains little of the radical Expressionism of the original.)

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts has some of the most avant-garde set designs of the era. Jagged white sets are smeared across back voids, as in the scene at the top where the protagonist flees down an endlessly winding road after being rebuffed by the woman for whom he impetuously stole money. It records another performance by one of the leading Expressionist actors of the era, Ernst Deutsch, whom I mentioned in my entry on Der Golem. Apart from its jagged sets, the film features a remarkable scene at a bicycle race, with the contestants being filmed in a distorting mirror. It was a technique that the French Impressionists would soon popularize, but Martin may have used it first (see left).

Despite the film’s lack of impact at the time it was made, it belongs squarely within the German Expressionist movement. This release at last allows it to take its place. (The forthcoming issue of the restored Expressionist science-fiction film Algol, also from 1920, will give an even broader picture of the movement.)

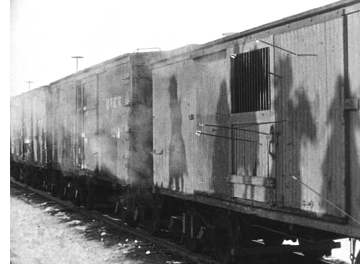

Eureka! Ford is found

The British company Eureka! continues to bring out classic films of all sorts. Its “Masters of Cinema” series has released John Ford’s 1924 western,  The Iron Horse. By this point in his career, Ford has made many western features, only a few of which survive. They were lively low-budget films, but by the early 1920s the western became a prestige genre with the success of James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon in 1923. The Iron Horse was Ford’s move into the high-budget western, and what it lacks in high-spirited energy it makes up for in impressive landscapes and careful dramatic staging. The Indian attack on the train, revealed by shadows (right) is one of the film’s high points.

The Iron Horse. By this point in his career, Ford has made many western features, only a few of which survive. They were lively low-budget films, but by the early 1920s the western became a prestige genre with the success of James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon in 1923. The Iron Horse was Ford’s move into the high-budget western, and what it lacks in high-spirited energy it makes up for in impressive landscapes and careful dramatic staging. The Indian attack on the train, revealed by shadows (right) is one of the film’s high points.

This Eureka! release is the same version and has the same extras as the DVD in the American series “Ford at Fox.” The two-disc set includes both the 150-minute version released in the U.S. and a 133-minute version, with alternate takes, distributed abroad. Anyone in European Region 2 area who doesn’t want to buy the immense “Ford at Fox” set of 21 discs might want instead to pick up The Iron Horse, one of its highlights, separately. It has plenty of extras as well.

I’ll sneak in an early sound film by recommending another Eureka! release of just about a year ago, Max Ophuls’ La signora di tutti (Everybody’s Lady). Made in italy in 1934, it was Ophuls’ first film after fleeing the Nazi regime. It’s a flashback tale, with the heroine recalling her life after a failed suicide attempt. It’s a new transfer and comes with a video essay by Tag Gallagher and a booklet.

Do yourself, your family, and your friends a favor

The 1994 edition of the “Giornate del Cinema Muto” in Pordenone, Italy, was as memorable as usual. There was the magical presentation of all the surviving Indian films (apart from a few short scraps), accompanied by a delightful and inventive chamber group of three Indian musicians. There were the silent westerns of William Wyler and the sophisticated 1920s features of Monte Bell. The main thread, though, was “Forgotten Laughter,” a celebration of known, little known, and unknown comedians. Their films were mainly shorts, and they provided us with a great deal of laughter.

Then came Wednesday, October 12, when we all witnessed history. A program entitled “Max Davidson” unspooled five two-reelers starring a short, middle-aged guy doing a beleaguered-Jewish-father shtick as well as such a thing has ever been done. We enjoyed four films before the program culminated with the immortal Pass the Gravy. I don’t think I’ve ever heard an audience laugh so loudly and continuously. Don’t assume this is anti-Jewish humor. This is pure Jewish humor, injected for just a few years into mainstream American slapstick filmmaking.

For some reason that year there was a poll taken to determine a film which would be encored at the end of the final evening. Pass the Gravy inevitably won, and we laughed just as hard the second time through. Mere words cannot convey why this film is so funny. It involves Max’s  daughter being engaged to a young man who lives next door with his father, proud owner of a prize rooster which ends up the main dish in a meal shared by both families. The running gag involves the young people trying to convey to Max what has happened without the young man’s father realizing what has happened. But no, you have to see it for yourself, preferably with friends and family about you. Like so many comedies, this one works best with an audience.

daughter being engaged to a young man who lives next door with his father, proud owner of a prize rooster which ends up the main dish in a meal shared by both families. The running gag involves the young people trying to convey to Max what has happened without the young man’s father realizing what has happened. But no, you have to see it for yourself, preferably with friends and family about you. Like so many comedies, this one works best with an audience.

It has taken 18 years for the surviving Max Davidson shorts, most of them supervised by Leo McCarey, to appear on video, a two-disc set, “Max Davidson Comedies.” Fortunately the job has been done well. The Munich Filmmuseum has assembled 13 shorts, 12 silent and one sound. Not all are as funny as Pass the Gravy, and Max plays only a supporting role in the earliest one. (The less said of the sound short, the better.) A booklet, in German and English, includes historical background and complete credits, including descriptions of the lost films. Davidson, by the way, had a long career playing bit parts, often uncredited. Often he played tailors, as in The Idle Class and The Extra Girl; during the sound era he appeared in The Plainsman and The Great Dictator, among many others. But for a short stretch at the Hal Roach studios he was the star.

At this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival, “Max Davidson Comedies” shared the DVD prize for “Best Rediscovery of a Forgotten Film” with a parallel set put out by the Filmmuseum, “Female Comedy Teams.” The latter included more films shown in Pordenone in 1994.

Of course, the Davidson films were not forgotten by those of us lucky enough to have been in the Cinema Verdi in 1994. Two of them, including Pass the Gravy, were shown on Turner Classic Movies at 6 am a few years later, and we long treasured our VHS tape of that. But now everyone can share in this rediscovery.

A modestly pioneering early American film company

The Kalem company was one of those firms that cropped up during the early years of the American film industry, made shorts and short features for less than ten years, and disappeared without growing into one of the important Hollywood studios. Today it is perhaps best remembered for its 1913 biblical feature, From the Manger to the Cross, which was shot in Egypt and “the Holy Lands” at a time when filming abroad was unusual for  American film companies.

American film companies.

Kalem had pioneered the tactic of filming abroad earlier, however. Its series of films shot in Ireland, beginning with The Lad from Old Ireland (1910), are claimed to be the first American films shot outside North America. Eight of these survive, though often with missing sections. The Irish Film Institute has released a two-disc set including all of them, along with a feature-length documentary, Blazing the Trail: The O’Kalems in Ireland, directed by Peter Flynn.

The films were shot in the region of the Lakes of Killarney, taking advantage of famous locales like the Gap of Dunloe and Torc Waterfall (seen in Rory O’More, right). Intertitles include passages emphasizing that the scenes were shot in the very places where their historical and literary sources were set.

Unfortunately even the surviving films are not in good condition. Some are lacking their endings, and all are worn. The transfer has unfortunately cropped the edges, even though the accompanying documentary stresses that director Sidney Olcott’s main strength was his eye for compositions. Still, this set of films provides a rare example of fairly standard American films of the transitional period between the primitive and classical eras. Most classes in cinema history represent this transitional period mainly through the Biograph shorts of D. W. Griffith. This DVD provides a chance to show the more mainstream filmmaking of the early 1910s.

The accompanying documentary, Blazing the Trail, takes its title from the memoirs of Gene Gauntier, Kalem’s main scenario-writer and leading lady in its early period, including most of the Irish-based films. The film is perhaps a bit over-long for the topic, but it provides a rare in-depth look at a small company of the early era. The DVD set is available only from the Irish Film Institute’s website.